This article about improving your students’ music reading through rote teaching is brought to you by guest writer Broc Hite. Broc is a church organist, piano instructor, and website developer based in Northwest Arkansas, USA. He grew up in New York, where he earned a BFA in Piano Performance from Purchase College and a MM in Collaborative Piano from The Juilliard School. Broc worked for many years as a software engineer/data analyst and earned his MBA at the Stamford campus of the University of Connecticut. He moved west for a job promotion 10 years ago. To learn more about Broc, visit brochite.com.

We as teachers are beholden to a written musical tradition that dates back to the year 1025 when Guido d’Arezzo introduced modern staff notation. Before Guido, there was still music. It just wasn’t as easy to share it widely.

When teaching, it’s easy for us to get caught up in Guido’s amazing system of notation which can convey so much of what is in the music. But it helps to take a step back and ask, “Which came first: The chicken, or the egg?” Or in our case, the music, or the notation?

The music did, of course.

Notation is just a necessary shorthand to convey that music to others. Why, then, do we always have to teach the notation before teaching the music?

We don’t.

In many cases, I believe it’s better to teach the music before the notation.

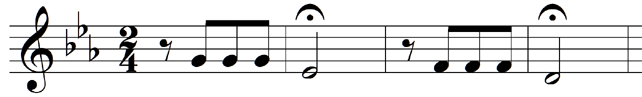

Think back to the first time you heard this iconic opening:

You don’t need to be able to read music to perceive it as three short notes leading to a stronger downbeat.

Imagine trying to explain this notation to a non-musician who had never heard the music. (Hey now, stop singing while you’re explaining it! They’re not supposed to hear it first, remember?! 😉)

If, however, they’ve heard the music first, it becomes much easier to explain how the notation fits to the sound.

Teaching music reading through rote song or demonstration is not cheating. Students have a much easier time absorbing the notation if they understand the music first.

Teaching Rhythm by Rote

Beginner Students

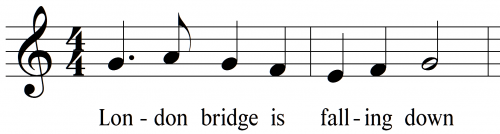

Here is another famous motif which you’ve likely encountered as a teacher:

How many of you have gotten to the dotted crotchet and quaver (dotted quarter and eighth note) and spent a good part of the lesson analysing and teaching this new bizarre rhythm before realising there must be an easier way?

Sure, an 8-year-old student might eventually catch on to the explanation (after much frustration and feelings of inadequacy.) But how would you teach it to a 4-year-old?

By imitation.

If you’re using a good method book, chances are that this rhythm will show up again a few more times, allowing you to add the understanding of how the notation fits the sound.

I wish I had figured this out sooner!

As a recent convert to the Piano Safari method, I noticed that this same rhythmic element appears in the pre-staff melody from Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.” Julie Knerr, one of the method’s authors, adds the footnote “teach it by rote.” No doubt she wants to save teachers like me from putting the notation before the music!

Late Beginners

Although late beginners often have the basics of standard note values down, certain new rhythms can really be confusing. Sometimes it’s just best to teach the new rhythms by rote, and then explain the notation afterward.

New Music Styles

Whenever you expose your students to new musical styles – whether they cross country or genre borders – you’re going to find new rhythms with new notation.

Introducing your student to jazz, rock, tango, or bossa nova with an aural demonstration is not cheating. It’s a direct pathway to understanding the music, which then leads to understanding the notation needed to express it.

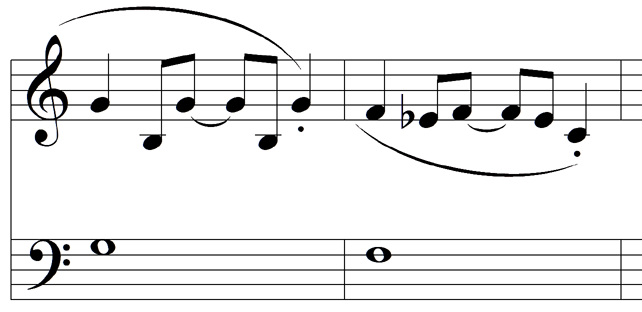

Take this calypso example I recently encountered with a student from the Alfred Premiere Piano Course Lesson Book Level 2B.

I spent about 5 minutes going through the clapping drill – using both metrical and Kodály counting – before finally just saying, “Listen and repeat.”

When I explained the notation later, it made sense because the student had already learnt the music.

Compound Time Signatures

Consider the introduction to compound metre. Folk music such as “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” and Irish jigs are two common types of music you’ll see written with compound time signatures.

Again, how would you teach this to a 4-year-old?

Once the music is understood, teaching common variations which tend to happen within 6/8 time – such as a crotchet (quarter note) followed by a quaver (eighth note) – makes much more sense.

Need more help teaching rhythm to intermediate students? Nicola’s Music Theory page is chock full of ideas!

Advanced Students

If you teach any teenagers who have played for some time, you’ll likely get into the truly complex rhythms which can occur in their music.

Pianists often face some very complex rhythms, thanks to composers who wish to create overlaying textures of sound.

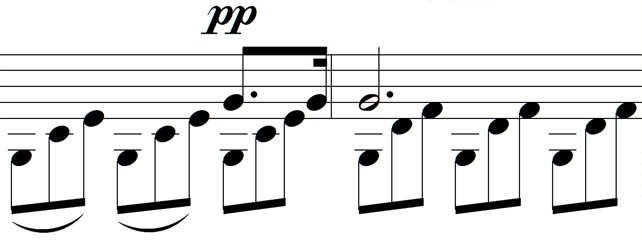

This example comes from a section of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata where there are frequent 4-against-3 textures:

Practising polyrhythms between the hands has its place, but this isn’t one of them. This is a perfect chance to boost music reading skills through rote teaching, as a quick demonstration typically brings about the desired result much more quickly.

You don’t have to analyse, like a scientist, the exact duration of the microsecond which occurs between the final triplet note and the semiquaver (sixteenth note).

The Score Can’t Capture Everything

Once you remember that the score came after the music, you realise that the score can’t capture everything.

If you’re playing music from the French Baroque, you will find notes that look like even quavers (eighth notes) but are meant to be played in the style called inégalité, where the first note is longer and the second note is shorter much like the quavers (eighth notes) in the swing jazz style.

Sometimes musical editors will point this out. Other times it’s up to you to learn the style, which you’re not going to get just from reading the page.

Even in what you might consider a staid form like the Viennese waltz, there’s a slight inflection to the beat which is not on the page.

The next time you hear any authentic group from the Vienna Philharmonic down to an oompah band, you’ll hear those seemingly even crotchets (quarter notes) played with an ever-so-slightly shorter first beat and corresponding longer second beat. Sometimes it’s more exaggerated than other times; it’s all in the musical style.

If you remember anything from this article, let it be this: Guido may have given us a tremendous hand, but he didn’t say to stop listening to the music!