The following article about teaching pop chord progressions is written by guest blogger Tony Parlapiano. Tony is a piano instructor and the creator of popMATICS, a concept-based music curriculum which approaches learning by listening and reading through writing. Tony resides in East Longmeadow, Massachusetts where he enjoys fancy coffee, plays in spreadsheets, and carries a copy of his birth certificate for anyone who questions the authenticity of his last name.

Well, it happened again. One of my high school students had a busy week and didn’t practise. I’m sure she wasn’t feeling great about coming to class unprepared, and I knew neither one of us would be thrilled with the idea of rehashing last week’s lesson.

When I sense my students are feeling overwhelmed by the demands placed on their time and attention, I want to ensure their lesson experience provides some relief. I’ve always believed that students can decide what they get to play without necessarily determining what they get to learn.

So, when little to no practice occurs between lessons, I often take the opportunity to level up their “learning-by-listening” skills using a favourite pop song of their choice.

It all starts when I hand over the iPad for a student to queue up the recording. As I prepare to begin teaching a song I’ve likely never heard before, you can feel the instant shift of energy the moment their selection comes pouring out of the speakers.

It reminds me of the opening lyrics to Bob Marley’s Trenchtown Rock: “One good thing about music: When it hits, you feel no pain.”

We remember pop songs based on the feelings they bring. Sometimes the emotional connections are so intense that specific songs become tied to our favourite moments from childhood, for couples, family vacations, or special occasions.

And just as hearing these songs can bring back memories, they can also protect the learning experience so that the lessons never leave the student.

Hearing Numbers

When teaching pop chord progressions, I take the approach of learning by listening. I want my students to think (and hear) in numbers before letters.

The benefit is that they only have to learn one number system. As they move through the keys, the letters representing each number will change but the underlying harmonic structure remains.

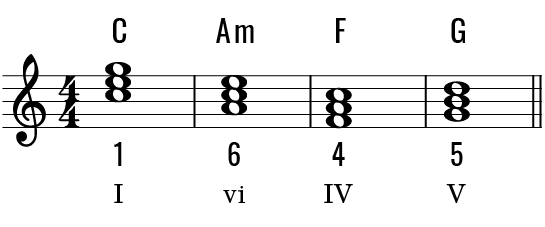

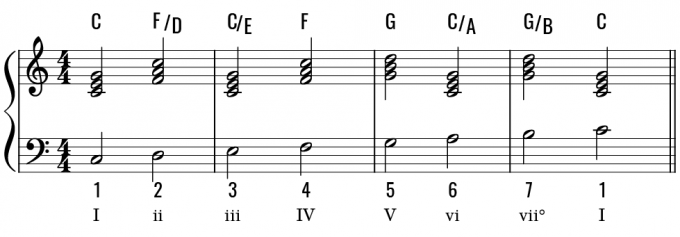

For example, let’s take the following chord progression:

It would be unfortunate for a student to learn this sequence without understanding that they are playing a Sixteen Forty-Five (1 6 4 5) in the key of C, especially since this is a standard progression which, with enough experience, can become easily identified through listening alone.

You may need to find a piano to discover the key, but you don’t need to know that to hear the movement of 1 to 6 to 4 to 5.

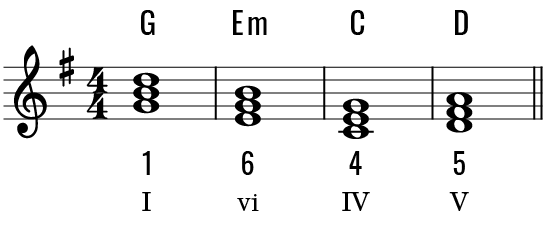

If we identify the key as G, our Sixteen Forty-Five will convert to the following:

Just as we construct every major scale with a half step between degrees 3–4 and 7–8, students must learn that the quality of chords within the key is also consistent. Knowing that 1, 4, and 5 are major, 2, 3, and 6 are minor and 7 is diminished is an essential element to understanding the basics of functional harmony.

In our examples above, you’ll notice that both of the Sixteen Forty-Five progressions include the chords C and G. However in the first example – the key of C major – C is 1 while and G is 5. In the second case – the key of G major – C is 4 while G is 1.

When students learn the quality of chords within the key, I like to show them how every major (and minor) triad will appear in precisely three keys. Since the 1, 4, & 5 chords are major, a C major triad will serve as each of those numbers.

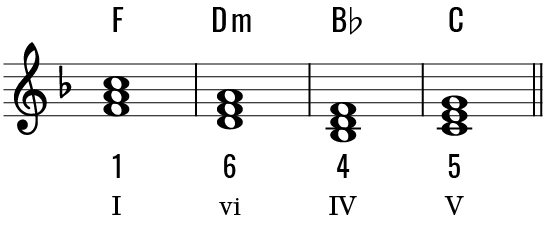

As revealed in our progressions above, C is 1 in the key of C major and 4 in the key of G major. If we convert our Sixteen Forty-Five to the key of F major, we discover that C represents the 5.

The four numbers that make up the Sixteen Forty-Five (1 6 4 5) will often show up in a different order.

In the song “Photograph” by Ed Sheeran, the intro and verse both loop a Sixteen Fifty-Four pattern (1 6 5 4), the pre-chorus follows a Sixty-Four Fifteen (6 4 1 5) pattern, and the chorus flips to a Fifteen Sixty-Four (1 5 6 4) pattern.

Magic Math: Turning 3 Chords Into 9

I’ve heard musicians joke that you can play every pop song ever written using just four chords: The 1, 4, 5 and 6 of any given key. While you can indeed play a lot of pop songs with just these four chords, I like to show students a little trick about how they can play even more with only three.

We achieve this by first identifying the primary (major) chords – the 1, 4 and 5 of any given major key. By stacking these three chords over various bass notes, we can create the nine most common chords which make up 90% of the stuff found in 90% of pop music.

For many songs, these nine chords will be everything you need and, by developing a comprehensive understanding of how they work together, it becomes easier to identify when something falls outside this structure.

In the following examples of teaching pop chord progressions, I will convert the numbers as they relate to the key of C major since it’s easy to visualize. We are going to break this system into two parts, starting with the primary chord scale.

The Primary Chord Scale

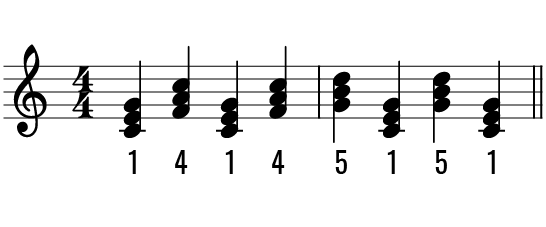

Before we dig into the theory, let’s hear it! In the right hand, play these chords:

Next, play those chords in the right hand over an ascending C major scale in the left hand to create the primary chord scale.

Voila! You’ve just played the seven most common chords heard in popular styles of music.

The next step is to practise these chords in groups so students can quickly recall which primary chords go with which bass notes. For this, I have students memorize the sequence #136 – 2457 using telephone number rhythm.

Write it on an index card, leave it on the piano, and tell them all about how when you were a kid, you didn’t have a cell phone and had to remember your best friend’s phone number. It’s important. Do it.

Now, contained within an octave, play those scale degrees as bass notes in the left hand. In the key of C, this will convert to:

C E A – D F G B

Tack on a C at the end to resolve the movement, just as you would complete an ascending major scale. The first three numbers (1, 3 and 6) go with the 1 chord. The next two (2 and 4) pair with 4 chords, and the last two (5 and 7) with 5 chords.

Resolve to the tonic, and this number system converts to:

Now that we’ve got the sound, let us take a moment to compartmentalize these seven chords.

The Basics

The primary chords – 1, 4 and 5 (or C, F and G) – remain unaltered.

The Minor 7ths

In a basic chord scale, 2 and 6 are already minor triads. 4/2 (F/D) and 1/6 (C/A) are minor sevenths in disguise.

By stacking the primary chords over the secondary roots, we’ve extended the harmony to include the minor seventh (the most common minor variant).

A chord chart doesn’t need to permit you to add them. In nearly every context, a minor seventh will not only work but enhance the sound.

In a lettered chord chart, a 4/2 (F/D) will read as Dm7 and 1/6 (C/A) as an Am7. Remember that every diatonic minor seventh chord can build as a primary chord over a secondary root.

Tip: For a neat assignment that’ll get students playing every minor seventh chord, take a look at a circle of fifths and play the major key as a major triad over the relative minor as your left-hand bass note, but I digress…

Slash Chords Substitutions

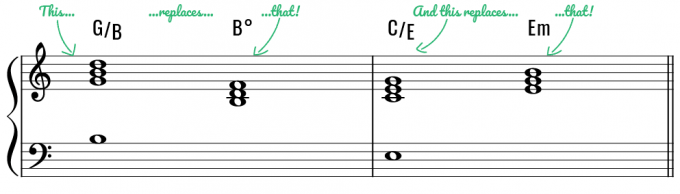

The 5/7 (G/B) and 1/3 (C/E) are common substitutions.

The 5/7 (G/B) replaces the 7 chord (Bdim) nearly 100% of the time.

The 1/3 (C/E) is a common substitution for the 3 chord (Em), though it doesn’t happen nearly as often as the trade of 5/7 for 7 does…

…which brings us to our alternate routes.

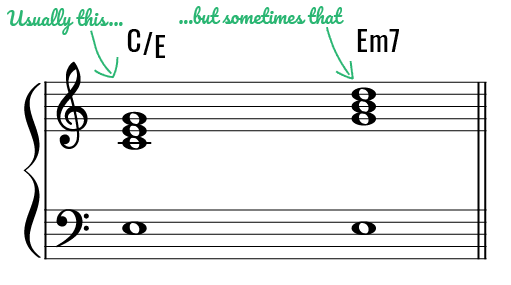

Alternate Routes: The Final Two Chords

While the seven chords which make up the primary chord scale represent a high percentage of what you’ll need to cover all your pop needs, two alternate routes need mentioning.

When you hear a 3 (E) in the bass, it is most likely going to pair with a 1 (C) chord. However, if that’s not the correct sound, it will probably come with a 5 (G) chord instead. This 5/3 (Em7) can be added to our collection of minor sevenths from above, since it’s the same math as our 1/6 (Am7) and 4/2 (Dm7).

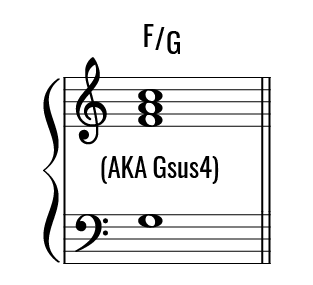

The final component to this number system is 4/5 (F/G), which is your pop dominant seventh.

Unlike the genres of classical and jazz, the traditional V7 is not so standard in pop music. More often than not, you’ll be working with a clean 5. However, the 4/5 happens often enough that it’s worth mentioning.

In a chord chart, you’re more likely to see 4/5 written as a “dominant seventh sus4” (G7sus4). Still, I prefer to present this as a slash chord, sticking with F/G.

So that’s it! With just three primary chords stacked over different bass notes, we have packaged the essentials for students to play the songs they know and love.

After all, isn’t that what teaching pop chord progressions is all about?

Variants

Variants are mods and extensions to the previously mentioned numbers. Some examples would be a 1(add9), 4(maj7), or a 5(sus4).

Covering all the possible variants is beyond the scope of this post, but what I’d like to mention is that students don’t need to catch all these details at the outset.

A 1(add9) is still a 1 chord. A 4(maj7) is still a 4 chord. A 5(sus4) is still a 5 chord.

Even when you’re reading from chord charts with these included details, students can always strip it back to the base number.

Yes, you may lose a bit of structural integrity, and some variants add a more defined colour than others, but these concepts should build on a solid foundation and understanding of the essentials.

Alternatively, you can always show a student where to place their hands to create necessary variants without digging too deeply into the theory.

Putting It All Together

Now, let’s get back to the student!

The chorus (her favourite part) is about to drop. She’s already forgotten about that chemistry test tomorrow, the essay due next Wednesday, and her track meet on Saturday. She’s in the moment and feeling the music.

Together you identify the key, establish bass motion, write down the numbers, stack the primaries, add variants (maybe), and convert the numbers to chord symbols for whatever key best fits her voice.

You might also transcribe any hooks or significant melody lines and, without launching a theory grenade, briefly discuss anything that falls outside the standard diatonic system.

Before you know it, your student has the basic structure in place and is connecting her voice to the instrument. You’ve delivered a positive and engaging lesson experience that sends her away happier than when she arrived.

While I often recommend this strategy for teaching pop chord progressions as a remedy for teachers wondering what to do with students who don’t practise enough, for me, it’s the principle method I use for ensuring students develop the necessary listening skills that keep them returning to the piano for life.

What’s fascinating about this approach of learning by listening is not only how much better your students get at picking out chords and melodies of the songs they know and love, but also how their song choices become more interesting.

Students begin to notice when a song is easy enough to figure out on their own and will start to request material with details and elements they haven’t heard before.

It sparks curiosity and enthusiasm – a brilliant testament to the power and goodwill of practising interest-led learning.

The next time your student shows up to class overwhelmed and unprepared, perhaps you can smile and sing the next line of the song:

“So hit me with music!”

To learn more about Tony Parlapiano and read more of his writings, visit parlapianostudio.com. And if you’re looking for more ideas about teaching chords you can use in your lessons, Nicola has some awesome resources on her music theory page.

LOVE this! Thanks for breaking it down so well.

Hey Dana! Thanks for reading! I’m so glad you enjoyed the post!

Wow. So awesome. Thank you for sharing.

Hey Rebecca! Thanks for reading! I’m so glad you enjoyed the post!

Thanks! I am registering for your site now.

Would you wait until students have already learned basics like major scale formula and qualities of diatonic triads before introducing this exercise? Or could you do this at the very beginning of lessons as a means of learning the theory?

Hi Barbara,

Thanks so much for reading! Yes, I start by introducing the major scale, basic chord scale, and primary/secondary chords before diving into the Primary Chord Scale w/Alternate Routes. I have another exercise called AREA 5(1) for beginners that follows a lot of the same concepts but simplifies the right-hand so students can focus their attention on the left-hand, which provides the most useful information when trying to identify the underlying harmonic structure.

-Tony

Tony,

Just stumbled across this via Google. What a great music theory article. You definitely have an ability to communicate ideas concisely while remaining engaging.

Enough blowing smoke 🙂 How about a follow-up blog, moving into the realm of jazz harmony by reharmonising pop progressions using your method?

Looking forward to you publishing a book.

The fact that “teaching what students find relevant” is considered unique shows exactly how and why American education has failed, thoroughly, for so long. Btw, teacher training programs in the US are uttervfaikures too.

Very useful and creative content thank you! Just a possible correction – wouldn’t 4/5 be written as a G9sus4 instead of a G7sus4?