Bringing up scales is one of the easiest ways to get piano teachers to close their eyes and sigh. If we all hate teaching piano scales, and our students hate playing them, can we just skip them altogether? Is this one aspect of the traditional piano lesson that we should throw out along with the 18th-century horsehair wigs?

⬆️ Listen to the podcast above or keep on reading, whichever fits your style. ↙️

I actually don’t hate teaching scales anymore. What I do hate is going to the hairdresser.

Most people talk about the hairdresser as if it’s a pampering experience. But for me, it’s anything but. My neck isn’t made for their sinks and the smells aren’t particularly pleasant…however, that’s not what really bothers me.

The uncertainty of the results is what makes me uncomfortably wring my hands together under the cloak of invisibility.

Despite attempting to learn all the lingo and say exactly what I said the last time I got a good haircut, I still never know what they will do. They often cut off too much (and it takes me half a century to grow it back since my hair is made of feathers and illusion) or they give me a style that really only works for straight hair – but on my curly hair, it looks like I’m dressing up as a pyramid for Halloween.

The sweaty palms, awkwardness and outward appearance of the polite calm required from me reminds me of being tested on scales and arpeggios as a teenager. I had no idea what the result would be back then, either.

What’s the point of scales?

I’m sure I’m not alone in these feelings so I’ll ask again, should we abolish them? What is the true value of teaching scales, anyway?

I believe there is enormous value, and I absolutely still include scales in my lesson plans. But when a student asks why we are doing them, my answer is not that it is good for technique. Because, after all, you can play scales with terrible technique if you want to, and teaching effective technique is a whole other topic.

Subscribe to the newsletter and get the Why Practice Scales infographic

Enter your details to subscribe to the newsletter for piano teachers with information, tips and offers.

I hate spam as much as you do! I will only send you emails related directly to piano teaching and you can unsubscribe at any time.

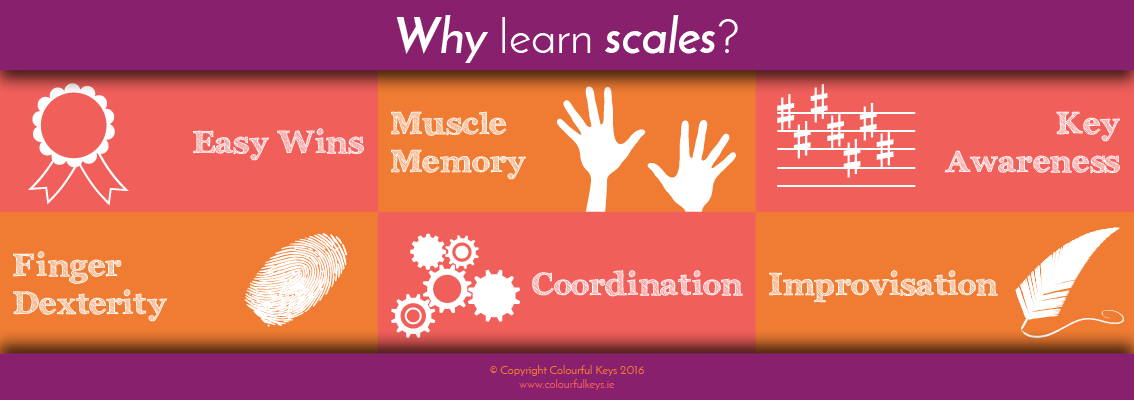

Scales are simply technical exercises. But they are one of the best technical exercises we can do, and there are 6 reasons they still reign supreme:

- Even touch and tone: Scales can be a great environment for learning to play with an even touch, if a teacher emphasises this

- Music theory: Learning scales and really understanding them gives students a great foundation in music theory.

- Sight reading: Good scale knowledge means students can read new music more easily, because they can spot common patterns quickly and chunk them into one piece of information rather than reading individual notes

- Muscle memory: Building our kinesthetic memory of the scale fingering patterns allows students to play pieces with greater speed and accuracy

- Aural skills: If we get our students to listen, scales can be a great environment for developing their ears

- Creating music: Since scales are the building blocks of music, if we know them well, we can easily compose and improvise in various keys.

If you’re already a VMT member, you can download this infographic from the printable library. Not a member? Learn more at vibrantmusicteaching.com.

How do most teachers teach scales?

The 6 reasons above provide a powerful argument in favour of teaching scales. But we still have an issue: they are not enjoyable for most teachers and students. So let’s examine how they are normally taught in order to find out why they are such a bore.

In most piano lessons, scale work looks something like this:

- C major, hands separately, focussing on the “thumb under”

- Hands together, similar and contrary

- The rest of the white keys – same method

- Battle through the black keys

- Go over and over and increase octaves

Even if you start with a similar key, this focus on fingering above all else means that this is what you get out of scales:

- Muscle memory

- Muscle memory

- Muscle memory

- Even touch and tone

- Sight reading

- Music theory

Aural skillsCreating music

Aural skills and creating music don’t even feature in this type of approach. It’s really about the patterns (in neat and tidy forms that don’t really appear in pieces) The other benefits of scales barely get a look-in.

What are YOUR true priorities when teaching scales?

Ask yourself these questions in order to reveal your priorities as they stand now:

- What do you stop to fix?

- What do you add as the next layer?

- Which bits do you run out of time for?

Ultimately, it doesn’t matter what you think about or even talk to students about. It matters what you do in your lessons – that’s what students will absorb.

So look at what you’re putting most emphasis on in your teaching of piano scales, and ask yourself whether that aligns with the reasons you consider to be the most important. (You know, those things that make you say, “Hell no!” to removing scales altogether.)

When I took a hard look at this several years ago, it didn’t add up. The benefits I got from scales in my own playing were not the goals I was modelling to my students. And it all made a lot more sense to me when I started to approach scales with improvisation first and fingering patterns later.

Today, my order of priorities goes something like this:

- Music theory

- Creating music

- Muscle memory

- Aural skills

- Sight reading

- Even touch and tone

Keep in mind that this is just what I want from teaching piano scales, not for my lessons overall.

You can find many, many more resources for teaching music theory on my hub page devoted to that subject.

How can we use this improv-first approach to scales?

The first step is to take away your preconception of what counts as “scale work”. Starting with improvisation means that you need to allow students to use free fingering. Wrong notes won’t need to be corrected; students will hear when a note doesn’t belong in the key and quickly adjust.

Circle-of-Fifths Odyssey

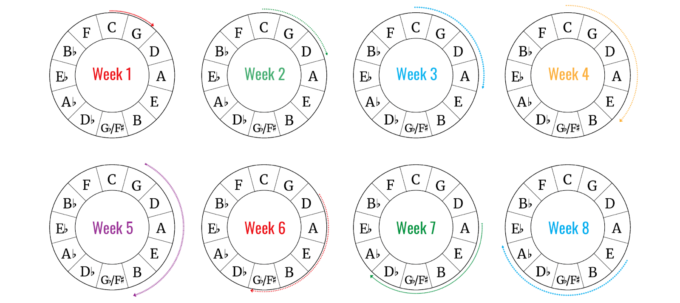

Inside my Vibrant Music Teaching membership for music teachers, I have a course called the Circle of Fifths Odyssey. This online course for teachers includes lesson plans with many detailed components, but the basic premise is very simple:

We go on a journey, one key signature at a time, around the circle of fifths.

In week 1, we improvise in C major and G major. Every week after that we add one new key. We always improvise in multiple keys in each lesson (ideally 3 – 5) so students can get a feel for the relationship between keys and what it means to use a certain scale or play in a certain key.

In the picture above, you can see how this activity might progress over 8 weeks. I haven’t gone all the way to 12, though, as I think you get the gist from the first 8. 😉

How to Accompany Student Improvisation

In my opinion, the best improvisation accompaniments are very simple. Here are some examples of the kinds of patterns I would play.

If you’re a chord wizard and you want to get fancier, that’s fine. Just keep in mind that you are not the star of the show. You want to play something that makes your student shine and gives them space to explore.

Where do we go from here?

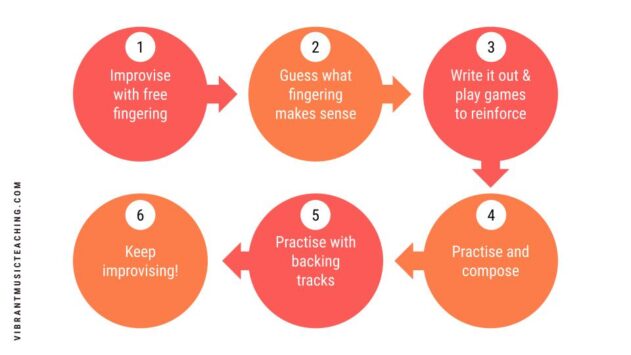

Improvisation is just the in-road. I absolutely want my students to learn scale fingerings and play them in different configurations. Here’s an overview of how this progresses over time:

We stay with just improvisation until the student has learnt to play legato with good technique and without tension. This may take years for some of my youngest students, or just a few weeks for older beginners.

The magic is that, although we may delay the introduction of scale fingerings, students who start with improvisation move far more quickly once they start learning “proper scales”. They already understand what scales are and the reasons for learning them, and I’m giving them space to work out the logic behind the fingerings so their brains are switched on the whole time. And engaged students learn much more quickly than daydreaming robots.

Will you give scale improvisation a try in your lessons?

If it seems intimidating or you’re feeling uncertain about it, just dip your toe in the water. Give it a go for 1 minute with 1 student in 1 lesson. Then try 2 minutes with 2 students the following week. Before you know it, you’ll be hooked!